HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a lentivirus (a member of the retrovirus family) that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in humans in which the immune system begins to fail, leading to life-threatening opportunistic infections. Infection with HIV occurs by the transfer of blood, semen, vaginal fluid, pre-ejaculate, or breast milk. Within these bodily fluids, HIV is present as both free virus particles and virus within infected immune cells. The four major routes of transmission are unsafe sex, contaminated needles, breast milk, and transmission from an infected mother to her baby at birth (Vertical transmission). Screening of blood products for HIV has largely eliminated transmission through blood transfusions or infected blood products in the developed world.

HIV infection in humans is considered pandemic by WHO. From 1981 to 2006, AIDS killed more than 25 million people. HIV infects about 0.6% of the world's population. In 2005 alone, AIDS claimed an estimated 2.4–3.3 million lives, of which more than 570,000 were children. A third of these deaths are occurring in sub-Saharan Africa, retarding economic growth and increasing poverty. According to current estimates, HIV is set to infect 90 million people in Africa, resulting in a minimum estimate of 18 million orphans. Antiretroviral treatment reduces both the mortality and the morbidity of HIV infection, but routine access to antiretroviral medication is not available in all countries.

HIV primarily infects vital cells in the human immune system such as helper T cells (specifically CD4+ T cells), macrophages, and dendritic cells. HIV infection leads to low levels of CD4+ T cells through three main mechanisms: firstly, direct viral killing of infected cells; secondly, increased rates of apoptosis in infected cells; and thirdly, killing of infected CD4+ T cells by CD8 cytotoxic lymphocytes that recognize infected cells. When CD4+ T cell numbers decline below a critical level, cell-mediated immunity is lost, and the body becomes progressively more susceptible to opportunistic infections.

Eventually most HIV-infected individuals develop AIDS. These individuals mostly die from opportunistic infections or malignancies associated with the progressive failure of the immune system. Without treatment, about 9 out of every 10 persons with HIV will progress to AIDS after 10–15 years. Many progress much sooner. Treatment with anti-retrovirals increases the life expectancy of people infected with HIV. Even after HIV has progressed to diagnosable AIDS, the average survival time with antiretroviral therapy (as of 2005) is estimated to be more than 5 years. Without antiretroviral therapy, death normally occurs within a year.

Classification

HIV is a member of the genus Lentivirus, part of the family of Retroviridae. Lentiviruses have many common morphologies and biological properties. Many species are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses with a long incubation period. Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon entry of the target cell, the viral RNA genome is converted to double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase that is present in the virus particle. This viral DNA is then integrated into the cellular DNA by a virally encoded integrase, along with host cellular co-factors, so that the genome can be transcribed. After the virus has infected the cell, two pathways are possible: either the virus becomes latent and the infected cell continues to function, or the virus becomes active and replicates, and a large number of virus particles are liberated that can then infect other cells.

There are two strains of HIV known to exist: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that was initially discovered and termed LAV. It is more virulent, relatively easily transmitted, and is the cause of the majority of HIV infections globally. HIV-2 is less transmittable and is largely confined to West Africa.

| Species | Virulence | Transmittability | Prevalence | Purported origin |

| HIV-1 | High | High | Global | Common Chimpanzee |

| HIV-2 | Lower | Low | West Africa | Sooty Mangabey |

Signs and symptoms

Infection with HIV-1 is associated with a progressive decrease of the CD4+ T cell count and an increase in viral load. The stage of infection can be determined by measuring the patient's CD4+ T cell count, and the level of HIV in the blood.

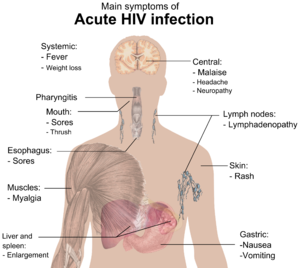

HIV infection has basically four stages: incubation period, acute infection, latency stage and AIDS. The initial incubation period upon infection is asymptomatic and usually lasts between two and four weeks. The second stage, acute infection, which lasts an average of 28 days and can include symptoms such as fever, lymphadenopathy (swollen lymph nodes), pharyngitis (sore throat), rash, myalgia (muscle pain), malaise, and mouth and esophageal sores. The latency stage, which occurs third, shows few or no symptoms and can last anywhere from two weeks to twenty years and beyond. AIDS, the fourth and final stage of HIV infection shows as symptoms of various opportunistic infections.

A study of French hospital patients found that approximately 0.5% of HIV-1 infected individuals retain high levels of CD4 T-Cells and a low or clinically undetectable viral load without anti-retroviral treatment. These individuals are classified as HIV controllers or Long-term nonprogressors.

Diagnosis

Many HIV-positive people are unaware that they are infected with the virus. For example, less than 1% of the sexually active urban population in Africa have been tested and this proportion is even lower in rural populations. Furthermore, only 0.5% of pregnant women attending urban health facilities are counselled, tested or receive their test results. Again, this proportion is even lower in rural health facilities. Since donors may therefore be unaware of their infection, donor blood and blood products used in medicine and medical research are routinely screened for HIV.

HIV-1 testing consists of initial screening with an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect antibodies to HIV-1. Specimens with a nonreactive result from the initial ELISA are considered HIV-negative unless new exposure to an infected partner or partner of unknown HIV status has occurred. Specimens with a reactive ELISA result are retested in duplicate. If the result of either duplicate test is reactive, the specimen is reported as repeatedly reactive and undergoes confirmatory testing with a more specific supplemental test (e.g., Western blot or, less commonly, an immunofluorescence assay (IFA)). Only specimens that are repeatedly reactive by ELISA and positive by IFA or reactive by Western blot are considered HIV-positive and indicative of HIV infection. Specimens that are repeatedly ELISA-reactive occasionally provide an indeterminate Western blot result, which may be either an incomplete antibody response to HIV in an infected person, or nonspecific reactions in an uninfected person. Although IFA can be used to confirm infection in these ambiguous cases, this assay is not widely used. Generally, a second specimen should be collected more than a month later and retested for persons with indeterminate Western blot results. Although much less commonly available, nucleic acid testing (e.g., viral RNA or proviral DNA amplification method) can also help diagnosis in certain situations. In addition, a few tested specimens might provide inconclusive results because of a low quantity specimen. In these situations, a second specimen is collected and tested for HIV infection.

Modern HIV testing is extremely accurate. The chance of a false-positive result in the two-step testing protocol is estimated to be 0.0004% to 0.0007% in the general U.S. population.

Treatment

There is currently no vaccine or cure for HIV or AIDS. The only known method of prevention is avoiding exposure to the virus. However, a course of antiretroviral treatment administered immediately after exposure, referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis, is believed to reduce the risk of infection if begun as quickly as possible. Current treatment for HIV infection consists of highly active antiretroviral therapy, or HAART. This has been highly beneficial to many HIV-infected individuals since its introduction in 1996, when the protease inhibitor-based HAART initially became available. Current HAART options are combinations (or "cocktails") consisting of at least three drugs belonging to at least two types, or "classes," of antiretroviral agents. Typically, these classes are two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NARTIs or NRTIs) plus either a protease inhibitor or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). New classes of drugs such as Entry Inhibitors provide treatment options for patients who are infected with viruses already resistant to common therapies, although they are not widely available and not typically accessible in resource-limited settings. Because AIDS progression in children is more rapid and less predictable than in adults, particularly in young infants, more aggressive treatment is recommended for children than adults. In developed countries where HAART is available, doctors assess their patients thoroughly: measuring the viral load, how fast CD4 declines, and patient readiness. They then decide when to recommend starting treatment.

HAART neither cures the patient nor does it uniformly remove all symptoms; high levels of HIV-1, often HAART resistant, return if treatment is stopped. Moreover, it would take more than a lifetime for HIV infection to be cleared using HAART. Despite this, many HIV-infected individuals have experienced remarkable improvements in their general health and quality of life, which has led to a large reduction in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality in the developed world. One study suggests the average life expectancy of an HIV infected individual is 32 years from the time of infection if treatment is started when the CD4 count is 350/µL. In the absence of HAART, progression from HIV infection to AIDS has been observed to occur at a median of between nine to ten years and the median survival time after developing AIDS is only 9.2 months. However, HAART sometimes achieves far less than optimal results, in some circumstances being effective in less than fifty percent of patients. This is due to a variety of reasons such as medication intolerance/side effects, prior ineffective antiretroviral therapy and infection with a drug-resistant strain of HIV. However, non-adherence and non-persistence with antiretroviral therapy is the major reason most individuals fail to benefit from HAART. The reasons for non-adherence and non-persistence with HAART are varied and overlapping. Major psychosocial issues, such as poor access to medical care, inadequate social supports, psychiatric disease and drug abuse contribute to non-adherence. The complexity of these HAART regimens, whether due to pill number, dosing frequency, meal restrictions or other issues along with side effects that create intentional non-adherence also contribute to this problem. The side effects include lipodystrophy, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, an increase in cardiovascular risks, and birth defects.

The timing for starting HIV treatment is still debated. There is no question that treatment should be started before the patient's CD4 count falls below 200, and most national guidelines say to start treatment once the CD4 count falls below 350; but there is some evidence from cohort studies that treatment should be started before the CD4 count falls below 350. In those countries where CD4 counts are not available, patients with WHO stage III or IV disease should be offered treatment.

Anti-retroviral drugs are expensive, and the majority of the world's infected individuals do not have access to medications and treatments for HIV and AIDS. Research to improve current treatments includes decreasing side effects of current drugs, further simplifying drug regimens to improve adherence, and determining the best sequence of regimens to manage drug resistance. Unfortunately, only a vaccine is thought to be able to halt the pandemic. This is because a vaccine would cost less, thus being affordable for developing countries, and would not require daily treatment. However, after over 20 years of research, HIV-1 remains a difficult target for a vaccine.